Being Antifragile with Sports Contracts

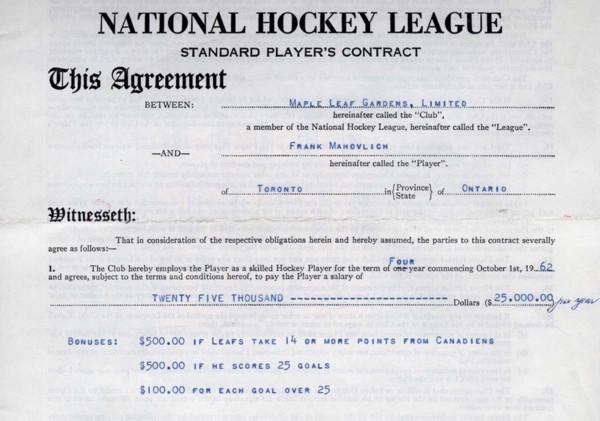

$25,000 contract! And look at that bonus for performing against the Canadiens.A few tweets popped into my timeline about how analytical types gauge contracts in hockey. I won’t go into specific player examples, but did want to make a few points about how teams can benefit from having small gambles with upside, rather than signing players with contracts that later become millstones if they don’t work out as expected for the team. Here are the tweets for context:

$25,000 contract! And look at that bonus for performing against the Canadiens.A few tweets popped into my timeline about how analytical types gauge contracts in hockey. I won’t go into specific player examples, but did want to make a few points about how teams can benefit from having small gambles with upside, rather than signing players with contracts that later become millstones if they don’t work out as expected for the team. Here are the tweets for context:

https://twitter.com/AdamZHerman/status/768810984521728000 https://twitter.com/hockeyanalysis/status/768812872440901632“THAT’S A BAD DEAL” will generally refer to contracts that have one or more of the following problems:

- Older player that is/will decline.

- Contract that costs too much for the player’s ability

- Contract term has too many years. Way too many times a team will give out these bad contracts and fail to realize how very hard they are to get out from under. These contracts are fragile, as defined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Fragility implies more to lose than to gain, equals more downside than upside, equals (unfavorable) asymmetry — Antifragile, Chapter 10In the NHL, contracts are guaranteed and thus your team is on the hook for the full duration and cap value. If it’s a long/expensive contract, you really need the player to live up that value. This means you’re starting behind before you get your first game out of the player! This also reduces your flexibility on the cap ledger and in the trade market. Other teams may not have the cap space to take on your player, or will give you worse players/draft picks in return. At the very best, he’ll slightly overperform: A $6 Million player who plays like a $8 Million player is nice, but it could be disastrous. (This is extremely true for goalies on long/costly contracts, signed after one good year)

On the flip side, David Johnson notes that a lot of times analysts expect a player to play above his contract and it doesn’t work out. This is a good thing! Sometimes you’re wrong, but if the contract is structured as follows, only upside can come from it:

- Young player with many elite years left.

- Contract has a low cap hit.

- Has only a few years on the contract. If you’re going to be wrong, it’s better to be wrong on a more flexible contract. Again to call upon Taleb, he would call these contracts antifragile:

Antifragility implies more to gain than to lose, equals more upside than downside, equals (favorable) asymmetry — Antifragile, Chapter 10You don’t give up a lot of cap space and the contract can be moved more easily. If you are correct, the upside is massive. The player could turn out to be a star and thus flipped to team for draft picks or you have a player playing at an $8 Million value for only $2 Million a year. At worst, you lose a few million. (And even then, there’s always space for 4th line guys on other teams, or they can contribute to the AHL team, so it’s never a huge loss)

Sports has a lot of volatility and a smart team can take advantage of that. Teams, especially those with limited budgets, must look to reduce their downside and increase their upside when it comes to contracts. A similar lesson is for teams to collect draft picks for cheap and young players. All else being equal, a few small failed contracts will certainly be worth the massive gain of a breakout player.

Let me know if you have any questions, please share, and lastly follow me on Twitter!